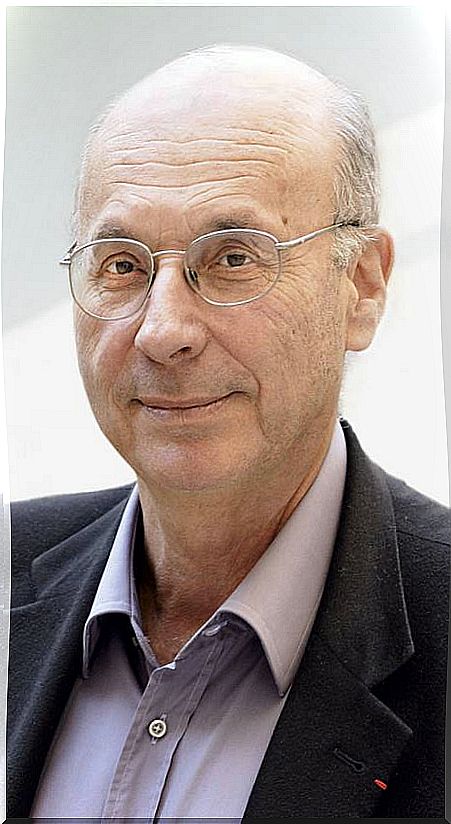

“I Became A Psychiatrist To Understand What Happened In My Childhood”

Neurologist, psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Boris Cyrulnik is the author of numerous successful works on the concept of resilience.

His personal story led Boris Cyrulnik to take an interest in the study of the human mind and to coin the concept of resilience, the ability to recover from trauma. His early childhood was spent in Bordeaux, until his parents were deported to Auschwitz.

At the age of five he lost his family and began his journey through various reception centers, escaping deportation and death several times, until he was adopted by a family with whom he recovered the world of affections. Then he became a famous psychiatrist.

–Did you choose the field of psychiatry because of your traumatic childhood?

–When we understand what has happened to us, we take possession of it; When we understand what has gone through the head of our aggressor, or of society, we take possession of our identity and we can once again find a space of freedom. That is why we see how Chile, for example, specializes in the construction of buildings against earthquakes, or that Italians specialize in volcanic eruptions. In the same way, many people who have had psychological difficulties are interested in psychology or psychiatry, since that allows them to understand the conflicts they have experienced.

– Is it only possible to overcome the trauma if others help us?

– I believe that we cannot live alone. Overcoming a trauma depends, in part, on the attachment and the type of affective relationship that the person had before experiencing said episode; it depends on the structure of the trauma and, above all, on the person’s family and cultural support after the event. If we have these three factors, the possibility of resilience, or recovery, is very high. But if after the trauma we do not receive help, the resilience decreases.

– Is it necessary to go back to the origins, complete one’s own story, if one has lived a childhood without parents?

– Forty years ago I would have answered that the most important thing is to look forward, not look back. It is what I did and, probably, what must be done to have a certain development … But today I think differently. I believe that our identity, that is, the representation we make of ourselves, depends on what we have done alone, but also on our family and culture of origin; therefore, we need to draw on those origins if we want to have a complete identity.

As an adult I couldn’t go back to Bordeaux because that place reminded me of the war, it was a forbidden city.

My university classes and the friendships I made in that city forced me to go every so often, but the negative feeling persisted… But, in 2008, visiting the house of the person who sheltered me for a while risking his life; the synagogue in which I was held and from which I escaped, avoiding being deported to the death camps and writing about it in the first person made me see the beauty of the city meant the end of the war sixty years later.

But before questioning ourselves about our past and completing our identity, we must repair ourselves.

–You say that the sense of humor helped you to de-dramatize the hardest moments of your childhood. Is laughter the best antidote to sorrows?

“When I was about six and a half years old, I was arrested by Gestapo agents wearing sunglasses in the middle of the night, their shirt collar turned up, and a hat, just like in bad movies.” They pointed a gun at me. I found that situation absurd and I told myself that adults were not serious people.

This humor helped me establish distance between myself and the assailant, even allowing me not to be traumatized by the arrest.

I was aware that I was condemned to death, but the meaning of death for a child of six and a half is not the same as for a child of ten or for an adult.

–When you were just a child, you had the courage to hide and escape to avoid deportation. He was very lucky…

–Yes, I have been very lucky. I think if I provoked it, it was probably because the years I lived with my mother, she gave me great confidence in myself. It is also true that, if I had not looked for it, luck would not have smiled on me.

“I suppose that avoiding death on several occasions has made him stronger.”

– I think that if I did not present psychotraumatic syndrome it was because I managed to escape and because of that day in January 1944 I keep the memory of having performed a feat. Every time I thought about what happened again, I said to myself: “Don’t worry, everything will be fine, there is always a solution.” That’s why I became a good climber, I could climb wherever I wanted just by saying to myself: “If you can climb, you can change your luck. Freedom is at the end of your effort ”.

–How did you manage to recover the past in a stringy way if you were so small and you were in so many places and with different people?

-Before 1980, when I recounted my memories, people laughed and did not believe me. That is why I chose not to explain, to silence my past. But the cultural change that appeared in that decade made it possible to speak freely about the persecution of the Jews.

After the publication of my first book, I appeared on television and that made the people who remembered me, who had helped me hide, want to contact me.

At that moment I was able to hear his testimony and understand even better what had happened to me. But that was thirty years after it had happened.

–The positive message of your story is that even in the worst circumstances we can overcome and fight injustice. What is necessary for this to happen?

–The affection. We now know that newborns who do not receive affection have no opportunity to develop, that affection plays an essential role in intelligence. When I started medicine, they told us that only the scientific mentality counted and that emotions had to be eliminated. Affection has now been discovered to be the biological source of memory.

–What have you learned from your experiences?

–I became a psychiatrist because I thought that it would help me understand what happened in my childhood, but I found that totalitarians are usually balanced people, they are not mentally ill, they are good students, integrated into the system, but submissive to a single representation of the man, a totalitarian boss.

The problem is cultural, not psychiatric.

It is journalists, writers, filmmakers, philosophers, psychologists … who can influence people to wonder if there can be a single human representation. The answer is no. There is not a single man who can give a philosophical or religious theory that represents the entire human condition. So we can only find partial solutions and do it through debate, meeting. Even if it is not perfect, at least it will not be totalitarian.